Submitted by Lisa Graves on

—By Brendan Fischer and Lisa Graves

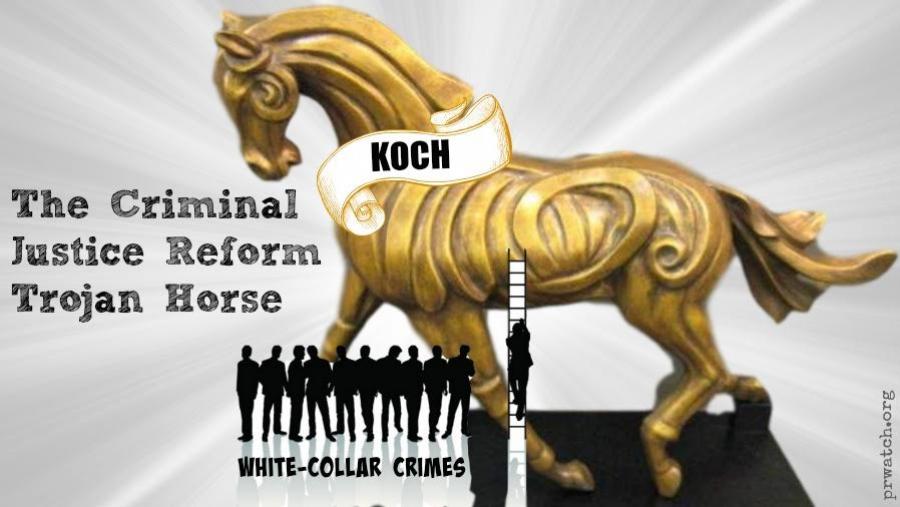

Charles and David Koch have received positive press for backing a bipartisan effort to reform American criminal justice laws, which have helped make the U.S. the world's biggest jailer and whose burdens have fallen disproportionately on people of color.

But, as the Kochs ride the wave of momentum toward criminal justice reform, it is becoming increasingly clear that part of their agenda would actually make it harder to prosecute corporate violations of environmental and financial laws that protect the public from corporate wrongdoing. The changes would make it harder to hold executives and their employees responsible for violating U.S. laws and would protect their financial interests, at the public's expense.

Over at least the past five years, the Kochs and Koch-backed groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) have been pushing to increase the "intent" standard for criminal violations, particularly for so-called "white collar" crime and executive suite criminals.

This under-reported aspect of the Koch criminal justice reform agenda has been elevated in recent weeks, and could potentially reap big benefits for Koch Industries and other big corporate players.

"Intent" Requirement Would Block Many Corporate Criminal Prosecutions

Legislation to make the criminal justice system fairer passed the U.S. Senate with bipartisan support this winter. As the U.S. House of Representatives has taken up the matter, the bipartisan consensus has begun to fray with a controversial proposal lifted directly from the Koch playbook.

A bill that passed the U.S. House Judiciary Committee last month, sponsored by Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI), doesn't address mass incarceration, one of the primary concerns that progressives have been raising for years. His bill would instead overhaul many federal criminal laws by requiring prosecutors to prove that a person or corporation "knowingly" engaged in illegal conduct and additionally "knew" or should have known that the conduct violated federal law. Koch Industries is one of his top contributors in this election cycle.

The bill's default criminal intent standard is strikingly similar to the ALEC "Criminal Intent Protection Act," and tracks policies promoted by Koch-backed organizations for the past five years. As the Center for Media and Democracy has documented, Koch Industries is a major funder and leader of ALEC, and the Koch brothers have underwritten ALEC through foundations they control and organizations they fund.

The proposal "would make it much harder for prosecutors to criminally prosecute companies that swindle the public, endanger their workers, poison the environment or otherwise imperil consumers," said Rob Weissman, President of the public interest group Public Citizen.

Criminal laws for acts of violence typically have an "intent" requirement, which requires that prosecutors prove that a person intended to cause harm and violate the law before a long prison sentence can be imposed. This intent requirement is known in legal terms as "mens rea," which is Latin for "guilty mind."

But for a number of white collar crimes, such as environmental violations and financial crimes under the Dodd-Frank financial reform law, federal law does not require that prosecutors prove that a company or its leaders intended to violate the law by polluting waterways, for example, or crashing the economy.

Instead, the fact of extensive pollution and the harms it causes can be enough to hold a corporation and its leaders criminally liable, because intent can be difficult to prove in a complex corporate structure, with varying layers of hierarchy and lines of authority. Corporate decisions rationalized in the name of cost-cutting or efficiency can lead to tragedies like the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster, which killed 29 workers. That case recently resulted in a rare criminal conviction for the former CEO of Massey Energy.

"Requiring that prosecutors prove that a corporate executive is both consciously aware of the conduct of their subordinates and consciously aware that the conduct of those subordinates violates criminal law is very, very difficult," said Frank O. Bowman, a law professor at the University of Missouri.

"This would make [white collar] prosecutions more difficult than they now are, and they are already hard," Bowman said.

Overcriminalization vs. Mass Incarceration

Although civil rights activists have been focused on mass incarceration—such as changing the mandatory minimum sentences enacted during the drug war that have disproportionately affected people of color, policies that scholars like Michelle Alexander have described as a "new Jim Crow"—the Kochs, ALEC, and other Koch-backed groups have been largely discussing overcriminalization.

Despite how it sounds, "overcriminalization" isn't focused on the disproportionate rate of incarceration of people of color. It is instead focused on the idea that there are too many crimes—and, more specifically, too many white-collar crimes that might affect corporate interests.

"All of the attention here is on whether this will only benefit quote-unquote white-collar criminals, people at financial institutions, people at firms that are damaging the environment," Jeffery Robinson, deputy legal director of the ACLU, said about the Sensenbrenner bill.

"If it only benefits those people, then I haven't seen any evidence that there is any over-incarceration among that group. In fact, we see very few prosecutions of such individuals."

That is, corporations and their leaders are not often federally prosecuted and convicted. In fact, many Americans have expressed deep disappointment that more corporations and bankers were not prosecuted following the gambling on Wall Street that led to the economic crash in 2008, unlike the nearly 1,000 prosecutions following the Savings & Loan crisis in the late 1980s.

"To a considerable extent, deferred prosecutions—in which the Justice Department agrees not to prosecute in exchange for a promise by corporate defendants not to violate the law in the future—have replaced actual prosecutions, undermining any kind of deterrent effect" for criminal penalties, Public Citizen's Weissman added. Deferred prosecutions are almost unheard of outside of the white collar crime context.

Some have expressed general concern that there are too many federal offenses with criminal penalties and too many that don't specify an intent standard, an issue that is being studied in the Senate bill. However, Koch-backed groups have been strongly focused on white-collar crimes, and their "solution"—the blanket imposition of a strict intent standard on every federal crime, as opposed to less-stringent "negligence" or "recklessness" standards—would undermine the few corporate criminal prosecutions that do take place.

For example, the U.S. Department of Justice has noted that—if the Sensenbrenner bill had been law—it could not have secured a guilty plea in last year's case against Jensen Farms, whose failure to follow food safety standards with its cantaloupe led to a listeria outbreak that killed 33 people. Imposing a default intent requirement could affect prosecutions for violations of laws like the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Resource Recovery and Compensation Act (RCRA), and many others.

And such changes could also make it harder to prosecute Koch Industries.

As Forbes noted, in 2000, "A federal grand jury indicted the privately held company and four of its employees in September on 97 related charges for alleged violations that took place at the company's refinery in Corpus Christi, Tex." Koch Industries was facing "criminal charges, in which the petroleum giant is accused of spewing the toxic chemical benzene into the environment in 1995 and then trying to hide it from government investigators."

Koch and its employees may not have intended to "leak" 91 metric tons of toxic benzene into the air and water around their refinery but their failure to install key protections and fully monitor their emissions resulted in their refinery loading 15 times the legal limit of the toxic substance into the environment.

That is, Koch Industries exposed nearby residents to massive amounts of benzene, which "is a well-established cause of cancer in humans." It is a "group 1" carcinogen because studies have documented that it causes acute myeloid leukemia in humans, and it may also cause lymphocyte leukemia, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. It can also result in reduced production of bone marrow and suppress T-cells, which makes people more vulnerable to infections. It has also been found to lead to chromosomal aberrations and can reduce birth weight and cause other health problems.

But then George W. Bush became president and John Ashcroft was named Attorney General. In the 2000 election, David Koch was one of the top 30 donors to Bush and the Republican party in the U.S., contributing $378,500 directly and an untold sum through soft money operations resembling the Triad group that was tied to the Kochs following a Senate investigation, as the Center for Media and Democracy has documented.

The Bush administration reduced the charges, which could have led to fines of more than $500 million, and dropped the case to just one count for a Koch Industries subsidiary, Koch Petroleum Group. "Under the plea agreement, Koch will pay a total of $20 million dollars: $10 million in criminal fines and $10 million for special projects to improve the environment in Corpus Christi—a record amount imposed in an environmental prosecution," DOJ stated.

It is this experience—the massive emission of a known carcinogen—that the Kochs say sparked their interest in criminal justice reform. Over the years, Koch Industries has been investigated for numerous potential violations of federal and state law. And the Koch reform efforts could help prevent such prosecutions from ever occurring again.

"Overcriminalization: Liberty, and More, At Risk for Corporations and Their Employees"

At times, the Kochs have been clear about the connection between "overcriminalization," a mens rea intent requirement, and their corporate interests.

In September of 2011, for example, Koch Industries' Associate General Counsel, Marsha Rabiteau, gave a presentation titled "Overcriminalization: Liberty, and More, At Risk for Corporations and Their Employees." She had given a nearly identical presentation two years earlier, titled then "Mens rea and other Criminal Law Fundamentals on the Tines of the Public Pitchfork."

That presentation, to a meeting of the Federation of Defense and Corporate Counsel, warned that:

"The life of the corporation, the liberty interests of corporate officers and other employees can be in the cross-hairs of criminal prosecution over matters that often do not rise to true criminal activity."

The solution to the "overcriminalization" problem, Rabiteau said, was to create a default mens rea requirement, as would later appear in the Sensenbrenner bill and in ALEC model legislation.

Rabiteau suggested that attendees visit the Koch-backed Heritage Foundation's "Overcriminalization" project (at overcriminalized.com) and cited a report from Heritage and another Koch-backed group, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, called "Without Intent: How Congress Is Eroding the Criminal Intent Requirement in Federal Law."

(Rabiteau also suggested that corporations, as a legal fiction, could not form the requisite "intent" to be held liable for a criminal act—although corporations and Koch groups have supported the creation of a right to corporate "free speech" in the form of spending unlimited amounts in elections.)

The Koch Associate General Counsel argued that reforming corporate criminal justice law is needed "so that wrongdoers are punished with laws that are clear and adhere to our Anglo-American heritage."

Although Rabiteau was likely referring to the country's "legal heritage," an appeal to "our Anglo-American heritage" to protect white collar criminals from criminal prosecution—when the burdens of an unjust criminal justice system have largely fallen on non-Anglo-Americans—further indicates the divide between the corporate criminal justice crusaders and civil rights-oriented reformers.

Moreover, America's legal heritage viewed corporate power with deep skepticism and for many years required that corporations have limited charters and durations to prevent them from misuse.

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Compromise, "Without Intent"

The Koch funding for criminal justice reform efforts ramped-up as the federal government began taking steps to reign in financial institutions following the collapse of Wall Street.

As the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill was being debated in 2010, two Koch-backed groups, the National Association for Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) and the Heritage Foundation issued a comprehensive joint report and project called "Without Intent" criticizing "overcriminalization" and the lack of intent requirements in the federal criminal code.

The co-author of NACDL's "Without Intent" report, which has been repeatedly cited in Congress' debate on criminal justice reform, is Tiffany Joslin, who is now Deputy Chief Counsel for the House Judiciary Crime Subcommittee, which is chaired by Rep. Sensenbrenner.

NACDL urged Congress to strike criminal provisions of Dodd-Frank that did not include an intent requirement, but Congress rejected that lobbying. When the law passed later that year, NACDL criticized the bill on these grounds:

"the overwhelming majority of the criminal offenses contained in the bill lack adequate mens rea, or criminal intent, requirements and, consequently, will fail to protect innocent or inadvertent actors from being criminally prosecuted or punished."

Why would the Kochs be concerned about Dodd-Frank and financial regulation? Because a big part of their multi-billion-dollar business comes from oil speculation. The Kochs have long been deeply involved in global financial markets, especially energy and commodity trading.

The Kochs are credited with creating the first oil derivatives in 1986. And they worked with U.S. Senator Phil Gramm to deregulate energy speculation with credit default swaps in 2000 with a measure that was later dubbed the "Enron loophole" after it aided the catastrophic collapse of the Texas energy giant. By 2009, a Koch executive boasted that the firm was one of the top five oil speculators in the world, with offices in London, Geneva, Singapore, Houston, New York, Wichita, Rotterdam, and Mumbai.

According to the Center for Public Integrity, the Kochs and their lobbyists "worked to favorably shape the [Dodd-Frank] bill, and have not stopped working since it was passed." Key aspects of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform bill attempted to bring transparency and stability to the $600 trillion "over-the-counter" derivatives market by dragging trades into the light of day, requiring supervision by a clearing houses, creating position limits for key commodities and requiring capital and margin requirements. Dodd-Frank also created some new criminal penalties, which were the focus of NACDL's objections.

On White-Collar Criminal Defense Lawyers….

The Kochs have received good press in recent months for acknowledging that they help fund NACDL (the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers), which does much more than promote better funding for underpaid public defenders representing indigent criminal defendants.

NACDL, in fact, has a substantial section devoted to aiding some of the wealthiest white-collar defense firms in the country and reshaping the law to address "overcriminalization."

Koch's Rabiteau, for example, urged others to "Join the Corporate Advisory Council to the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers White Collar Crime project" in her presentations to the Federation of Defense and Corporate Counsel. NACDL has also hosted Koch Fellows at its DC office.

And NACDL has been particularly focused on the mens rea issue in recent years, as the Kochs have ramped up their funding of criminal justice reform. For example, the current Director of NACDL's White Collar Crime Project, Shana-Tara Regon (now Shana-Tara O'Toole), has testified on Capitol Hill in favor of an intent requirement for white-collar crimes. She has also co-authored op-eds with the Heritage Foundation favoring intent laws, and has represented the organization on the "Congressional Task Force on Overcriminalization." And she addressed ALEC's criminal justice task force—apparently the only time that NACDL presented to that task force—about this very issue, criminal intent.

In 2011, NACDL's Regon testified before Congress in favor of reforming another white collar crime law, the 1977 Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), which prohibits U.S. corporations from bribing foreign public officials. She claimed that "the FCPA is emblematic of the serious problem of overcriminalization," and called for Congress to "strengthen the mens rea requirements of the statute." FCPA experts criticized Regon's call for adding an intent standard, describing it as a means of undermining the anti-bribery statute's enforcement and reducing incentives for companies to take affirmative steps to halt bribery.

At the hearing, Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) pressed Regon on how the FCPA could amount to "overcriminalization" when the Justice Department prosecutes an average of 14 cases per year. She replied simply that "a statute with no reasonable limitations is overcriminalization."

Notably, at the same time that Regon was testifying in favor of reforming the federal anti-foreign-bribery statute on "overcriminalization" grounds, the Kochs were embroiled in a bribery scandal in France.

Prior to the Kochs' public PR push on criminal justice this past year, few people outside of NACDL knew that it was funded by Koch money. The Koch role in funding NACDL as it advanced the Koch agenda on criminal intent changes did not come up during the hearing about those proposals.

The ALEC-SPN "Overcriminalization" Push

The year Dodd-Frank became law, in 2010, the Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) formed its "Right On Crime" project to make a conservative push for criminal justice reform, with "overcriminalization" one of its priority issues. TPPF is one of the "think tanks" that is part of ALEC and a sibling of ALEC, the State Policy Network (SPN), which has also been funded by Koch money and other funding vehicles used by the Koch network of billionaires.

Thanks to an accidental disclosure of TPPF's donor list, theTexas Observer reported that Koch Industries directly funded TPPF to the tune of $160,000 that year, as did the Kochs' Claude R. Lambe Foundation, which gave $70,000. Funding from Koch Industries or the Kochs themselves is not publicly reported so it is not known whether Koch Industries or the Kochs funded TPPF in prior or subsequent years.

When the "Right On Crime" launched its website on this project in early 2011, the group made clear that a major focus was "Overcriminalization," which it described on the front page of its website as "The Criminal Prosecution of Corporations."

Right on Crime's first post on overcriminalization warned that "criminal prosecution of corporations has gotten out of hand" and decried the prosecution of Arthur Andersen in the Enron case.

The "conservative solution" to overcriminalization, Right on Crime stated, was to "Stop creating new criminal offenses as a method of regulating business activities. Regulation is better handled through fines and market forces, not the heavy stigma of criminal sanctions."

The Koch-backed ALEC soon jumped on the "overcriminalization" bandwagon. ALEC, which bragged in the 1990s that it successfully spread "three strikes you're out" and "truth in sentencing" bills that helped increase the number of prisoners and the length of time served in prison for a variety of crimes, was now decrying the lack of a mens rea requirement for white collar crimes. For years, ALEC not only pushed for bills that increased the prison population but it also pushed numerous measures to privatize prisons, which benefited its corporate funders like Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). As part of its pay-to-play operations, when Walmart started funding ALEC, ALEC also pushed bills to create mandatory minimum sentences for shoplifting, enacted new penalties for retail theft, and even added sentencing enhancers for using an emergency exit when shoplifting.

But, in April 2011, ALEC held a presentation called "Overcriminalization: Not a Fair Fight: The Perils of Vague Criminal Statutes," featuring Regon, the head of the white-collar crime division of the Koch-backed NACDL. ALEC's agenda stated that "This presentation will discuss the proliferation of criminal law which has produced scores of criminal offenses that lack adequate "mens rea" (criminal intent) requirements. This discussion will provide legislators solutions to this attack on individual liberty and economic growth in their state."

A few months later, ALEC adopted the Criminal Intent Protection Act as a "model" bill for states. This bill—like Rep. Sensenbrenner's federal proposal—would impose a strict criminal intent requirement for any state criminal offense that doesn't specify otherwise.

Early the following year, in January of 2012, ALEC adopted a "Resolution on Transparency and Accountability in Criminal Law" decrying that "the creation of new criminal penalties is often obscured because these penalties are buried in legislation that is thousands of pages such as the convoluted Dodd-Frank bill enacted by Congress."

In 2013, ALEC released a report titled "Criminalizing America: How Big Government Makes a Criminal of Every American" urging state legislators to create a default mens rea requirement, specifically by enacting the ALEC "Criminal Intent Protection Act."

The report itself suggested ALEC's wanted a mens rea requirement because the corporate-backed group was concerned about average Americans. Yet ALEC showed its hand in a blog post announcing the report—they specifically noted that a default criminal intent requirement would affect the Clean Water Act, the same law that Koch Industries was accused of violating in 2000, writing that:

"to convict someone of violating the Clean Water Act, a prosecutor must only show that the accused has committed an infringement of the Act. Therefore, a person who did not know their conduct was illegal, or whose conduct was accidental, could find themselves facing criminal charges."

The New Jim Crow?

Notably, around the same time that the Kochs were ramping-up their spending on corporate-centered criminal justice policies, Michelle Alexander published her seminal book, "The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness," which helped push the problems with mass incarceration into the mainstream national consciousness.

That 2010 book detailed how the war on drugs effectively enforced a racial caste system, undermining many of the gains of the civil rights movement.

"No other country in the world imprisons so many of its racial or ethnic minorities," Alexander wrote. "The United States imprisons a larger percentage of its black population than South Africa did at the height of apartheid."

At the same time that discussions about mass incarceration and "The New Jim Crow" were making their way into the popular imagination, Koch-backed groups like ALEC were working to institute another policy with echoes of the original Jim Crow era: voter suppression policies, like voter ID restrictions that make it harder for Americans to vote. As federal courts have documented, such restrictions have a disparate impact, blunting the voting power of people of color. ALEC proponents of such bills have attempted to justify such restrictions by citing the virtually nonexistent threat of voter fraud.

Notably, the high-level Koch operative currently leading the Koch network's domestic spying outfit, Mike Roman, built his career helping to perpetuate the myth of voter fraud, helping to propagate race-baiting voter fraud hucksterism after the election of Barack Obama as president.

Kochs Ride the Wave of Criminal Justice Reform and Score Positive Press

The conversation around criminal justice reform has shifted over the years.

Even as crime rates dropped, prison populations were growing and were costing states a significant amount of their budgets. The private prison industry was pushing to add new revenue streams through expanded detention of immigrants. After an expose by Beau Hodai showing the controversial SB 1070 was adopted at an ALEC conference before it was introduced in the Arizona legislature, CCA stopped funding ALEC (and claimed it did not vote on that bill though it was present for the secret vote), and ALEC stopped pushing prison privatization on legislators.

Around that same time, states were facing substantial budget challenges following the Wall Street crash, and "conservative" politicians were more open to concerns that had been raised for years by progressives that many states were spending more on prisoners than on school children. A number of religious groups had also expressed concerns that mass incarceration was not leading to rehabilitation. And, the so-called "war on drugs" was increasingly recognized as a failure, as a number of jurisdictions began pursuing marijuana legalization measures. Addressing the crisis of mass incarceration has also been a key plank of many civil rights organizations' policy platforms.

As the racial justice aspects of criminal justice reform became mainstreamed—and as the Kochs became increasingly focused on burnishing their public image—the Kochs began to reframe their criminal justice efforts, and reaped some PR benefits, in the aftermath of a mountain of negative press about the extent of their efforts to reshape the U.S. political system for their own benefit.

Some in the press have even treated the Kochs as civil rights activists, despite Charles Koch having been a member and funder of the John Birch Society through the 1960s, even running a JBS bookstore stocked with books attacking Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement as communist, as CMD has documented.

The Kochs have received accolades for supporting a bipartisan coalition promoting criminal justice reform on the federal level, and have also received positive press for their funding of NACDL, with most news outlets focusing on NACDL's indigent defense work and overlooking NACDL's substantial white-collar crime work that aligns with the Kochs' interests.

"Everything we do is designed to help people improve their lives, whether you're talking about our business or our philanthropy," Koch General Counsel Mark Holden asserted to The Atlantic in March.

When the U.S. Senate passed a bill earlier this year that primarily benefited the Americans most affected by harsh criminal justice laws, it might have appeared the Kochs' criminal justice push was genuine.

Yet with Koch-backed politicians in the House now insisting on a mens rea requirement that would benefit Koch Industries—and which is the fruition of years of Koch-funded efforts—it is becoming increasingly clear that the Kochs are interested in more than altruism.

"Is there an element of self interest there? Probably," said Bowman, the Missouri criminal law criminal professor. "But," he asserted, "it is probably less prominent than the most suspicious of my liberal friends would expect."

"There is absolutely no reason for the otherwise laudable criminal justice reform bill to contain any measure to weaken already feeble standards for corporate criminal prosecution," said Public Citizen's Weissman.

It would seem prudent to view Koch support for criminal justice reform with a skeptical eye, once more than a merely superficial view of their efforts is examined.

The overwhelming focus of Koch-backed groups has been on criminal justice issues that would directly benefit Koch Industries and other corporate interests. Koch financial support for measures that would not affect their bottom line appears negligible, especially in comparison to the Koch Network's plans to spend $900 million this election cycle. Indeed, Charles Koch is notorious for insisting on a return on his investments in the public policy arena, and he's been called "relentless in pursuit of his goals."

And the Kochs have been outspoken about their support for political candidates like Scott Walker, who oppose criminal justice reforms that would help communities of color and others affected by harsh criminal justice laws. Among other things, Walker pushed ALEC's truth in sentencing into law in Wisconsin as a state legislator and ALEC member, helping make Wisconsin the worst state in the country when it comes to racial disparities in incarceration. But that didn't stop Koch Industries from maxing-out on contributions to Walker's 2010 gubernatorial campaign or David Koch's Americans for Prosperity from spending $10 million supporting Walker during the 2012 recall elections.

And, the Kochs have spent significant sums helping to elect judicial candidates using messaging that studies have shown have pushed judges to hand-down harsher sentences, along with other ads.

The U.S. criminal justice system is genuinely in crisis, and for too long has devastated families and communities. The stakes are too high to do nothing when there is bipartisan support.

But, given the Kochs' corporate interests in changing the criminal intent requirements, and the heavy push for such a change by groups and politicians they fund, there appears to be good reason for concern that "reform" efforts could be a Trojan Horse, as Dan Froomkin put it, to allow white-collar criminals to get off the hook for financial and environmental crimes that hurt countless Americans.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 256.89 KB | |

| 103.74 KB |

Comments

Gregory Kruse replied on Permalink

appreciation

Mike replied on Permalink

White collar?