Submitted by Mary Bottari on

A JPMorgan Chase employee stepped onstage at a black-tie gala on Wall Street last week to accept a "best crisis management" award given by an investor relations magazine. The bank, which was recently the subject of a U.S. Senate investigative hearing and an ongoing FBI probe into $6.2 billion in trading losses known as the "London Whale" fiasco, is not the subject of ridicule -- but praise -- from its cronies on Wall Street.

A JPMorgan Chase employee stepped onstage at a black-tie gala on Wall Street last week to accept a "best crisis management" award given by an investor relations magazine. The bank, which was recently the subject of a U.S. Senate investigative hearing and an ongoing FBI probe into $6.2 billion in trading losses known as the "London Whale" fiasco, is not the subject of ridicule -- but praise -- from its cronies on Wall Street.

Kathy Hu, from JPMorgan's investor relations department, accepted the award and quipped: "Crisis? What crisis?"

That's the kind of jokester you get to be when you work for a "too big to jail" bank, which repeatedly misled the public, investors and regulators about the ballooning crisis in its Chief Investment Office. The firm's lies are detailed in a 301-page report and 597 pages of exhibits prepared by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations chaired by Senator Carl Levin, only a portion of the 90,000 documents the committee gathered.

The committee's report details how America's largest bank and the largest derivatives trader in the world used "excess" deposits, including some that were federally insured, to construct a $157 billion portfolio of synthetic credit derivatives to engage in high-risk, complex, short term trading strategies. These are of the type that was supposed to be prevented by the "Volcker Rule," which was included in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform bill to limit proprietary trading by firms (the rule still has not been implemented).

As Senator John McCain so aptly put it: "These excess deposits should have been used to provide loans for main-street businesses. Instead, JPMorgan used the money to bet on catastrophic risk."

The Senate committee has done its job, now will New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman finally hold JPMorgan executives accountable?

Securities Fraud

It is against federal law and New York's powerful Martin Act for issuers of securities to make untrue statements or omissions of material fact in connection with the sale or purchase of securities.

On April 5, 2012, Bloomberg News broke the story that JPMorgan Chase was the mystery bank behind massive, distorting trades that were roiling world markets. The French-born London trader and JP Morgan employee Bruno Iksil was dubbed "Voldemort" and "London Whale" long before his identity was disclosed.

On April 13, 2012, JPMorgan hosted a regular earnings call and prepped talking points for participants. On that call, JPMorgan Chief Financial Officer Douglas Braunstein reassured investors, analysts, and the public that the activities of the Synthetic Credit Portfolio (SCP) were made on a long-term basis, were transparent to regulators, had been approved by the bank's risk managers, and served a hedging function that lowered risk and would ultimately be permitted under the Volcker Rule whose regulations were still being developed. Meanwhile, CEO Jamie Dimon dismissed the media reports as "a tempest in a teapot."

None of these statements were true. Below we quote liberally from the Senate report:

More than a Tempest in a Teapot. In response to a question, CEO Jamie Dimon dismissed media reports about the SCP as a "tempest in a teapot." While he later apologized for the comment, "the evidence indicates Dimon was already in possession of information about the SCP's complex and sizable portfolio, its sustained losses for three straight months, the exponential increase in those losses during March, and the difficulty of exiting the SCP's positions."

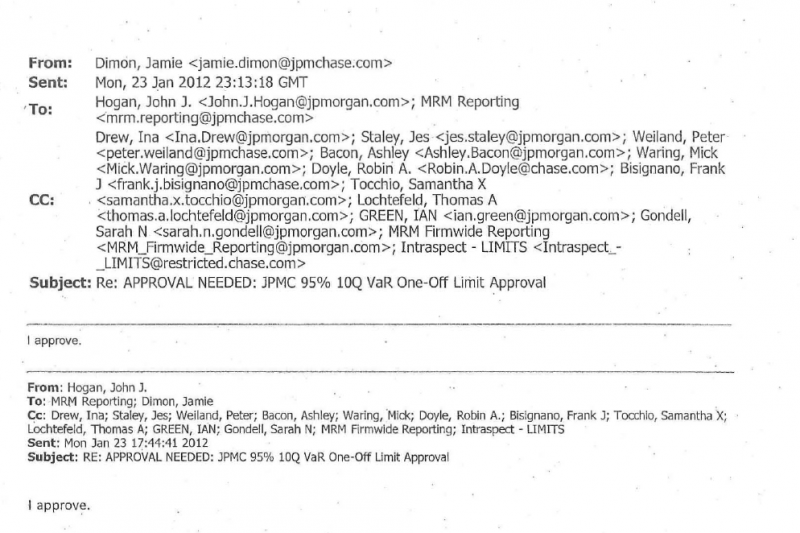

Omitting Risk Model Change. Near the end of January, the bank approved use of a new Value-at-Risk (VaR) model that cut in half the purported risk profile of the portfolio, but failed to disclose VaR model changes on numerous occasions. The change in the VaR methodology effectively masked significant changes in the portfolio. Dimon personally approved changes to the VaR model as seen in an email below and on page 363 of the exhibits.

Mischaracterizing Involvement of Firm-wide Risk Managers. Braunstein stated that "all of those positions are put on pursuant to the risk management at the firm-wide level." The evidence indicates, however, that in 2012, JPMorgan's firm-wide risk managers knew little about the SCP and had no role in putting on its positions

Mischaracterizing the Portfolio as "Fully Transparent to the Regulators." Braunstein said that the SCP positions were "fully transparent to the regulators," who "get information on those positions on a regular and recurring basis as part of our normalized reporting." In fact, according to the Senate investigation, the SCP positions had never been disclosed to bank regulators in any regular bank report. (Dimon also played a role in the withholding of regular profit and loss reports from federal regulators).

Mischaracterizing Portfolio Decisions as "Made on a Very Long-Term Basis." Braunstein also stated that with regard to "managing" the stress loss positions of the portfolio "[a]ll of the decisions are made on a very long-term basis." In fact, credit traders engaged in daily derivatives trading. "His description was inaccurate at best and deceptive at worst," concluded Senate investigators.

Mischaracterizing "Whale" Trades as Providing "Stress Loss Protection." Braunstein indicated that the portfolio was intended to provide "stress loss protection" to the bank in the event of a credit crisis, essentially presenting the portfolio designed to lower rather than increase bank risk. But the statement was contradicted by others at the firm.

Asserting Trades Were Consistent with the Volcker Rule. Braunstein concluded with: "[W]e believe all of this is consistent with what we believe the ultimate outcome will be related to Volcker." But the bank had earlier written to regulators expressing concern that the derivatives trading would be "prohibited" by the Volcker Rule.

Two-Tier Justice

JPMorgan borrowed some $68 billion from U.S. taxpayers and the Federal Reserve at the height of the 2008 financial crisis. It has been forced to pay out some $8.5 billion in settlements related to its role in the crisis (12 percent of its net income in recent years) and more lawsuits are in the works, yet no high level executive at JPMorgan (or indeed any American mega bank) has been brought to justice for these legal breaches.

The only people more corrupted than "the too big to fail" banks, and the U.S. Department of Justice which has decided to give them a pass, are Members of Congress who eagerly curry their campaign contributions and hand them the tools to create more havoc. Last week, the House Agriculture Committee held a markup on seven bills related to derivatives trading. The bills would grant a Congressional blessing to almost every reckless and illegal action JPMorgan Chase took in the London whale fiasco, arguesDavid Dayen in Salon.

Schneiderman, who ran for office with the support of the liberal establishment in New York, was supposed to usher in a new era of accountability on Wall Street. With the U.S. Department of Justice immunizing the big banks by embracing a two-tier system of justice, it is time for Schneiderman to step up to the plate. The Martin Act and the proximity of Wall Street give his office ample jurisdiction. In 2012, Schneiderman was appointed by President Obama to co-chair a federal task force to root out corruption at the big banks, but the task force was seemingly all for show, and Schneiderman has taken up too few cases independently. Now departing Senator Carl Levin has handed him a gift, with a big fat ribbon.

By putting participants under oath and gathering reams of documents, taped phone calls, emails and online chats, Senate investigators engaged in a major public service. Imagine how much more could be learned if the same participants were called to testify in a New York criminal investigation.