Submitted by Anne Landman on

The November 6, 2007 election brought a stinging defeat to Oregon's cigarette tax increase. The proposal aimed to raise the state's cigarette tax by 84.5 cents a pack to pay for health insurance for about 100,000 additional poor Oregon children who currently have no coverage. Measure 50, as the tax was called, went down by a wide 60-40% margin.

The November 6, 2007 election brought a stinging defeat to Oregon's cigarette tax increase. The proposal aimed to raise the state's cigarette tax by 84.5 cents a pack to pay for health insurance for about 100,000 additional poor Oregon children who currently have no coverage. Measure 50, as the tax was called, went down by a wide 60-40% margin.

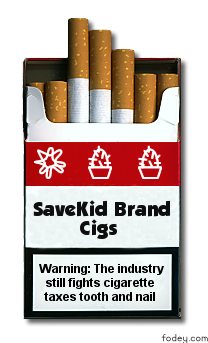

Increasing cigarette taxes to fund health care is not a new idea, and tobacco industry efforts to defeat such measures aren't new either. What was new in this case was that tobacco interests poured a record $12 million into defeating Oregon's measure, making it the costliest election in Oregon's history. So stunning was the industry's effort that Oregon Governor Ted Kulongoski openly accused the tobacco industry of "buying the election" in his state.

Old Dog, No New Tricks

The tobacco companies trotted out their most formulaic and time-tested strategies to defeat Oregon's tax measure: They created front groups with grassrootsy-sounding names designed to push voters' emotional buttons. R.J. Reynolds formed Oregonians Against the Blank Check, and hired their longtime Oregon lobbying ally Mark W. Nelson to head the group. Philip Morris formed "Stop the Measure 50 Tax Hike," and funded it with money from their parent company, Altria Corporate Services. The companies then determined which populist-sounding messages pushed voters' buttons the hardest while omitting any mention of the subject of health. They then purchased vast quantities of advertising to push these messages relentlessly onto Oregon voters.

It apparently worked, in spades.

The tobacco industry has been skewering Oregon's health measures using this very same formula -- and the very same guy -- for over 25 years. The industry's association with ballot initiative hit-man Mark Nelson dates back to 1980, when Nelson worked with a firm the industry hired to help defeat an early clean indoor air initiative in Oregon. The industry tapped Nelson again in 1987, when the Tobacco Institute enlisted his firm, Public Affairs Counsel (PAC), to defeat yet another Oregon clean indoor air measure. The relationship continued into the 1990s, when the industry hired Nelson to help defeat cigarette taxes in Oregon. A 1996 industry strategy document titled Proposed Advertising Strategy to Defeat Measure 70 was authored by an anti-tax Oregon tobacco industry front group called "Fairness Matters to Oregonians." It offers a road map to how the industry defeats cigarette tax ballot initiatives. Fairness Matters was headed by none other than Mark Nelson, who back then served as the campaign director for the Tobacco Institute's Oregon Executive Committee (OEC), a state-level subset of the Tobacco Institute created specifically to defeat cigarette tax increases in Oregon. The OEC was supported through contributions from Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds, Lorillard and the American Tobacco Companies. In another 1996 anti-tax industry strategy document, Nelson boasts that his company "has successfully managed and defeated every anti-tobacco initiative put forward in Oregon since 1988."

While industry documents describe how the tobacco companies defeat tax ballot measures, some questions remain about the industry's involvement in Oregon. Interestingly, in recent years the industry has been rolling over for cigarette taxes in some states. Why, then, did they come down so hard in Oregon in the last election?

Hammering Oregon, AWOL in Colorado

In 2004, Colorado citizens got an initiative on the state ballot to increase the cigarette tax by 64 cents. Like Oregon's Measure 50, the tax was to fund children's health insurance and other health-related programs. Also, like Oregon, Colorado's tax was proposed as an amendment to the state's Constitution. The reason, proponents gave, was to assure that legislators wouldn't be able to divert the cigarette tax funds to unintended purposes. Major health groups supported the tax in Colorado, just as they did in Oregon. The strange thing was that tobacco industry interference in Colorado's election was virtually absent. Some estimates claimed the industry put only about $10,000 into fighting Colorado's 2004 tax measure. In the absence of interference, Colorado's tax sailed through and passed by a wide margin. So why would the industry let a cigarette tax slide in Colorado, but come down like a ton of bricks on a strikingly similar measure in Oregon just a few years later?

There may be several reasons.

For one thing, the tax proposed in Oregon was relatively high. It would have brought the total cigarette tax to $2.02/pack, the third highest in the country, behind only Rhode Island and New Jersey. That might have seemed excessive to voters. Colorado's tax, at 64 cents a pack, was carefully calculated to rank the state exactly in the middle of all the states' cigarette taxes, undercutting any argument the industry could have rolled out that the proposed tax was too high. Another reason might have been timing. Colorado hadn't been successful in raising its cigarette tax since the late 1980s. By contrast, Oregon's last tax increase was in 2002, when Measure 20 increased the cigarette tax by $0.60, for a total of $1.28. Maybe the industry thought it was just too soon to increase the cigarette tax again in Oregon. Another factor was the saga of the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) bill. The U.S. House and Senate had just voted to raise the federal excise tax on cigarettes 61 cents to increase funding for children's health care (SCHIP). The passage of that bill through both houses showed a unique political consensus building to fund children's health care using cigarette taxes. The only thing that stopped the bill was one person, President Bush, when he vetoed the bill. Aware of the gathering trend in both the state and federal governments, the industry needed to send a forceful message that policies taxing cigarettes to fund children's healthcare aren't as easy to pass as it seems. Also, Oregon has a relatively small population compared to other generally anti-tobacco coastal states like California or New York, making it a much less costly place for the industry to ply this message.

Perhaps the most persuasive argument against the tax, though, was the idea advanced by the industry that a cigarette tax is the wrong vehicle to fund health care. Quite frankly, this argument does make sense. If cigarette smoking continues its decline, cigarette sales can be expected to decline into the foreseeable future, and the flow of cigarette taxes into state coffers will also decrease. Meanwhile, healthcare costs in the U.S. have been skyrocketing for decades. Funding a health care program with a revenue source that is known to be decreasing makes no sense. Using a cigarette tax to fund a program whose costs can be expected to decrease as cigarette use decreases would make far more sense. Examples of this might include nicotine addiction/smoking cessation treatment, home oxygen, respiratory or heart medications, beach cleanup, or even fire service equipment (since cigarette-caused fires would be expected to decrease as cigarette use decreases). Also, focusing a tax increase specifically on children may be politically expedient, but there are so many adults lacking access to adequate health care that they may be feeling left out by the ubiquitous focus on "our kids." Perhaps a significant number of lower-income voting adults are finally starting to feel ignored when it comes to the health care equation. Of course everyone cares about "our kids," but shouldn't we also care about the dilemma faced by all Americans who are being hurt by the current dysfunctional health care situation?

One sure factor contributing to the failure of Oregon's tax is that the public still doesn't understand that the economic costs to society of smoking far outweigh any taxes placed on the product in any state. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) every pack of cigarettes sold in the U.S. drains $7.18 out of the economy in medical care and productivity costs. The social costs of smoking, which also include fire injury and damage, excess litter, cleaning and ventilation costs, are borne by all of us. If you can reduce tobacco use while raising revenue, it will be a net plus for the economy, no matter how you look at it. But people still don't clearly understand that tobacco companies privatize the profits from cigarettes while letting society as a whole pick up the costs of smoking.

In any case, what happened in Oregon demonstrates that despite its declining popularity, the tobacco industry still wields tremendous influence at the ballot box when it decides to get involved in elections. It also reminds us that tobacco companies and their surrogate PR companies are still nothing short of masterful at manipulating how people think about their products, and the issues surrounding them.

Comments

Anne Landman replied on Permalink

More thoughts on Oregon and Colorado cig tax initiatives...

Anonymous replied on Permalink

As one of the Oregonians